In our last Callout Summer School class, we examined how to use Burn to determine when a song has reached the end of its life as a current hit. In today’s class, we tackle the other end of a song’s life as a hit—it’s beginning—and how to use Familiarity to judge when a song’s appeal is still growing.

As is standard practice in music testing, Integr8 Research asks listeners if they have ever heard of each song. They don’t have to know the artist or title. They don’t have to recall the words. The song merely needs to ring a bell to be “familiar.”

If a listener can’t recall ever hearing the song, she checks “unfamiliar” and moves on to the next hook.

On the surface, Familiarity is the easiest score in callout to understand: If a song’s Familiarity is 70%, it means 70% of listeners have heard the song—and 30% haven’t. Some firms report Familiarity (70%). Some report “Unfamiliar” (30%).

Understanding how to make decisions based on a song’s Familiarity is far less cut and dry.

GETTING TO KNOW A SONG IS LIKE GETTING TO KNOW A FRIEND

Think about your friends and acquaintances that you’ve gotten to know over the years. When you first meet someone, you might recognize their face or recall where you met them. (If you’re lucky, you might even remember their name.) However, you likely don’t have a strong opinion of them. “They seem nice,” you might say. In contrast, you likely didn’t consider anyone a “close” friend until after many encounters getting to know them deeply.

Just as you usually don’t get to know someone when you first meet them, people don’t truly “know” songs instantly, either.

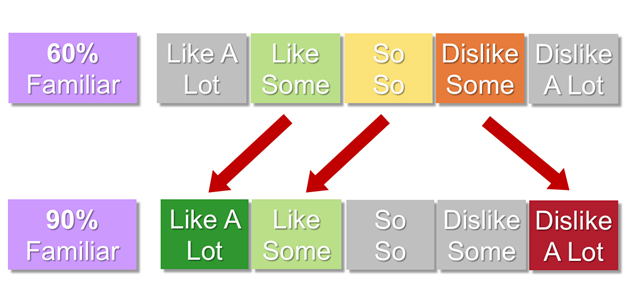

If a song is still unfamiliar among a significant portion of your audience, those listeners that do recognize the song likely still don’t know the song very well. That means even listeners who recognize the song likely don’t yet have a strong, set-in-stone opinion about that song.

In practical terms, listeners who only barely know a new song will typically rate it in the middle of the scale—they neither love it nor hate it. After hearing the song more and more:

- That same listener that once rated the song a “4” on a 5-point scale might decide they love it and rate it a “5”.

- A listener who originally had no opinion about a song (“3”) might grow to like it (“4”).

- A listener who at first thought the song was mildly annoying (“2) might grow to downright hate the song (“1”).

As songs become more familiar, listeners’ opinions about the song become more concrete

That’s why most songs that are highly unfamiliar also are the least popular songs even among those listeners who know them.

In contrast, songs that almost all of your listeners know are also songs your listeners really know—and they know if they love them or hate them. (After all, you have to know someone pretty well to consider them your enemy).

HOW TO USE FAMILIARITY

Here’s a general rule of thumb for translating how many of your listeners are familiar with a song to how well your audience truly “knows” a song—and how you should treat a song at each familiarity level:

Below 60% – This song is in the very early stages of its development. Even those listeners who do know the song probably don’t have strong impressions of it yet. Expect songs that less than 60% of your listeners know to be near the bottom of your callout ranker—but ignore these early results if you believe the song has hit potential.

Between 60% and 70% – Listeners know these songs better than your newest titles, but are still forming their opinions of them. While you might reject a song that listeners downright hate, songs in this familiarity range still have room to grow more popular.

Between 70% and 80% – The appeal level of these songs is stabilizing and you can now start using appeal scores to weed out songs that aren’t destined to become big hits. Keep in mind, though, that there are listeners who still don’t know these songs when you schedule them.

Between 80% and 90% – Listeners have formed their opinions about these songs are they probably are reaching the peak of their appeal. Furthermore, these songs are well known enough that you can power them.

Over 90% – These songs have become universally known hits, so much so that many of your recurrent-vintage songs will be in this range of familiarity.

The bottom line: Don’t rule out a new song your audience barely knows simply because it scores poorly in callout. Low familiarity indicates that listeners are still getting to know the song—and the song still has room to grow.

WHAT ABOUT SPIN COUNTS?

Many programmers began their careers using spin counts to determine when a song should be familiar enough to power and when a song should be burned enough to move to recurrent. However, what really impacts a song’s development isn’t how often you play a song, but how often your listener hears a song. With so many changes in how listeners consume music, yesterday’s spin benchmarks are no longer reliable metrics for making such decisions.

We do a deep dive in the way to think about exposure in our blog series How Often Do Listeners Hear Your Hits, especially in our post Why Song Familiarity is Like a Leaky Bucket.

In our next Callout Summer School class, we’ll show you how to create your test list for new music research, including common mistakes programmers make when choosing which titles to test.

Integr8’s exclusive Hitcycle® measure precisely tells you where each song is in its development cycle among your listeners—so you’ll have confidence when a new song needs more time to grow and when it’s time to move a song to recurrent. Contact us to learn how Hitcycle is better than Burn and Familiarity for picking the right new music.

Integr8’s exclusive Hitcycle® measure precisely tells you where each song is in its development cycle among your listeners—so you’ll have confidence when a new song needs more time to grow and when it’s time to move a song to recurrent. Contact us to learn how Hitcycle is better than Burn and Familiarity for picking the right new music.