Turn on your local hit music station right now. There’s a good chance you’ll hear a song from the last decade.

Sure, there’s consensus that new music is in a rut. (We explained why new music won’t suck forever in our previous post.) While we’ve seen plenty of new music slumps come and go at predictable intervals in the past, there’s a new phenomenon we’re seeing this time around.

Enter the Superhit.

A superhit is a hit that seems to stay a hit forever. From Ed Sheeran’s “Shape Of You” to Dua Lipa’s “Levitating,” these songs stick around a lot longer than we’ve seen songs last in the past.

It’s not your imagination that these superhits were not a thing until recently.

A superhit—for our comparison purposes—is a song that remains in the Billboard Hot 100’s Top 10 for more than 26 weeks. Before 2010, only one song ever stayed among the chart’s elite for over half a year: 1997’s “How Do I Live” by LeAnn Rimes, which lingered in the Top 10 for 32 weeks.

Starting in the 2010s, however, three superhits emerged:

- 2011’s “Party Rock Anthem” by LMFAO ft. Lauren Bennett and GoonRock (29 weeks)

- 2014’s “Uptown Funk” by Mark Ronson featuring Bruno Mars (31 weeks)

- 2016’s “Closer” by The Chainsmokers featuring Halsey (32 weeks)

Then in 2017, the floodgates opened for the superhit. That year alone, three songs stayed Top 10 for 27 weeks or more:

- “Shape of You” by Ed Sheeran (33 weeks)

- “That’s What I Like” by Bruno Mars (28 weeks)

- “Perfect” by Ed Sheeran (27 weeks)

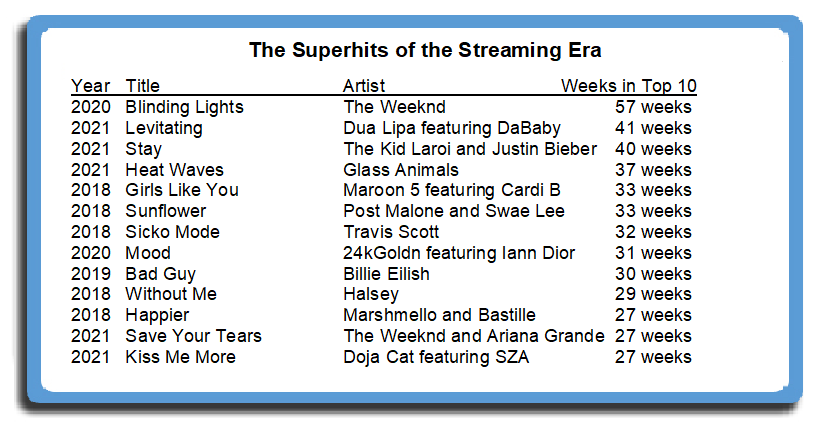

Since then, 13 songs have become superhits from 2018 to today.

What changed?

Has new music been so bad lately that listeners are holding on to these big hits?

Is radio no longer considering burn scores to move big hits out of heavy rotation?

Is the TikTok generation less interested in contemporary music as they resurrect everything from Kate Bush to Edison Lighthouse?

You’re overthinking it.

The superhit is a direct result of streaming—specifically—the way streaming measures music appeal differently than we used to measure it:

Before streaming, our understanding of what songs people loved most stemmed from the music they bought and the songs they heard on the radio.

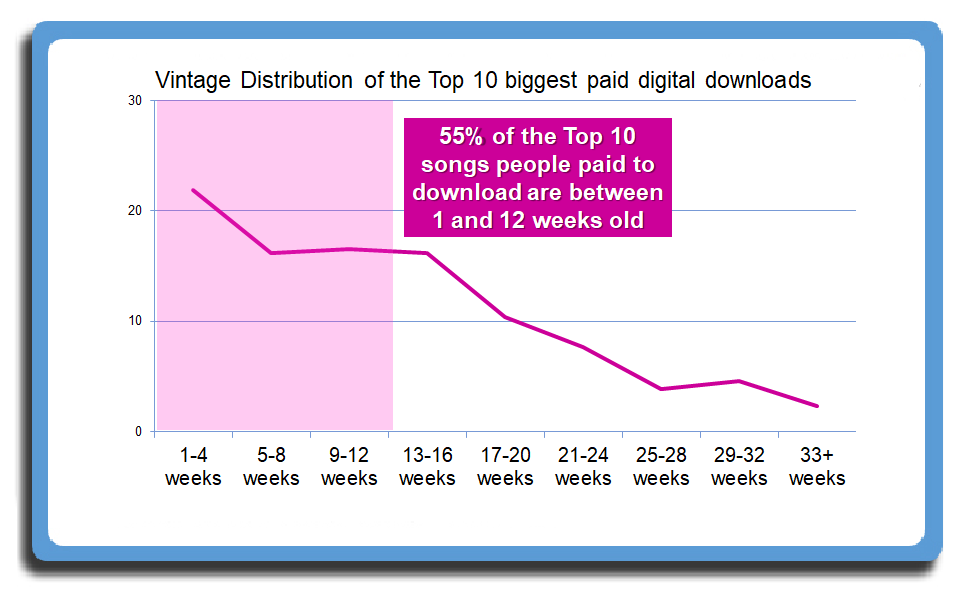

- Music sales is inherently front-loaded—that is, the top 10 best-selling songs tend to peak when they debut, and most songs are no longer top 10 in sales after 12 weeks. That pattern has remained remarkably stable from 45s through Cassingles to iTunes downloads. Why? People who already bought a song may continue listening to it for months—even years—but once new listeners stop buying a song, that song no longer charts.

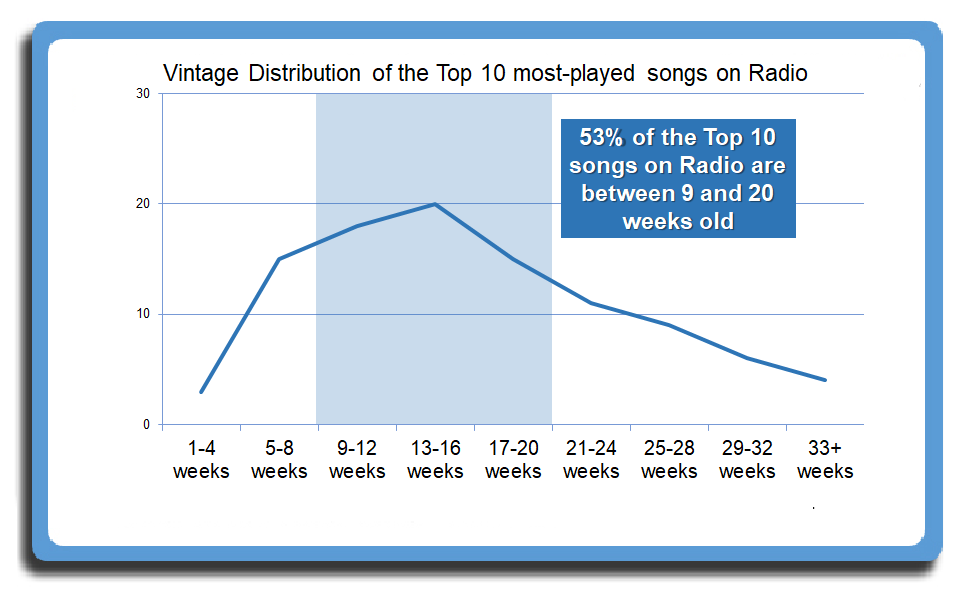

- Radio programmers, mindful that some listeners get tired of hearing months-old songs all the time, have historically moved songs to a lower-rotation recurrent category by the time songs are 26 weeks old. Such songs might still be the station’s best-testing songs in callout, but because stations air them less frequently, they’re no longer among the 10 most-played songs on the radio once stations move them to recurrent.\

This combination of sales being intrinsically front-loaded and radio backing off songs to avoid burning out listeners means, historically, songs simply didn’t stay in Billboard Hot 100’s Top 10 for more than 26 weeks.

Until Streaming.

The two fundamental changes that streaming data introduces are

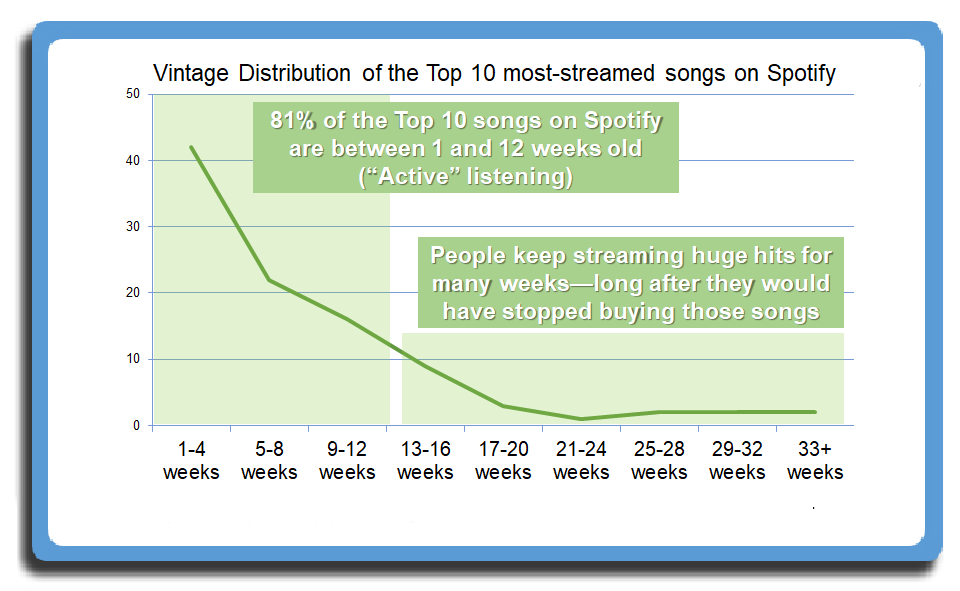

1) Plays, not people: Streaming measures how many times a song plays, not how many different people play a song,

2) Streaming includes active and passive consumption: Since people use streaming like a record store and like a radio, it mixes together both the active consumption we used to measure through song sales and the passive fandom we used to chart through radio airplay.

Just like radio listeners, streaming users also get tired of hearing hit songs over and over again at some point. At some point, even the most massive hits will receive a few fewer plays with each passing week. As long as enough people still play a song often enough, that song will remain among the most-streamed songs.

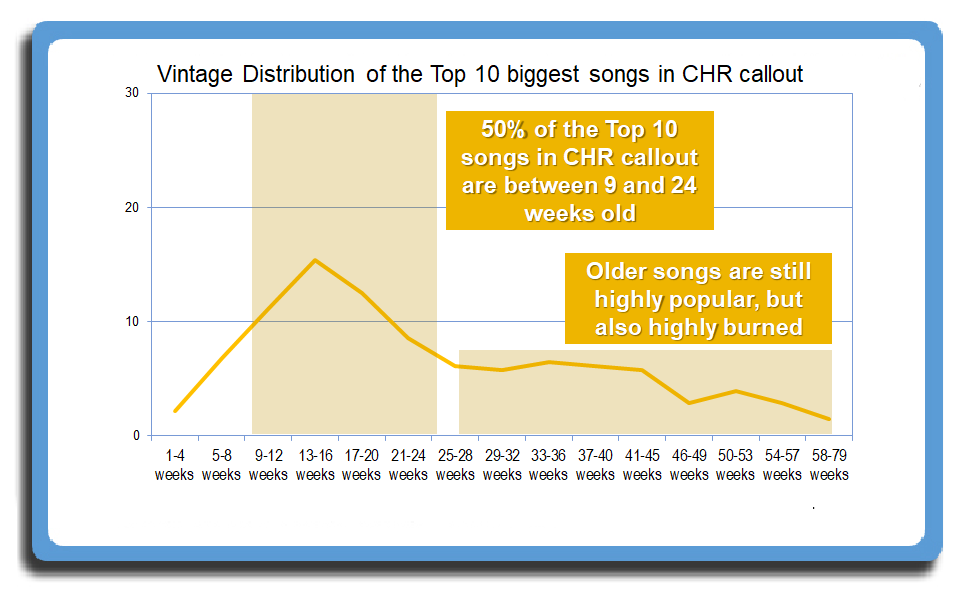

The superhits that people keep streaming week after week are usually also the songs listeners keep rating among their favorites in radio stations’ callout research week after week. Such songs existed long before the advent of streaming.

So why did the superhit explode in 2017?

Streaming plays were already a part of the Hot 100 metric starting in 2007. This change came during the digital download era. While “Party Rock Anthem” and “Closer” achieved superhit status due to heavy consumption on streaming, iTunes sales were still bigger than Spotify.

As 2017 became 2018, streaming overtook paid digital downloads as the dominant way consumers accessed new releases.

In some cases, a song became a superhit by being big with different audiences at different times.

- Billie Eilish’s “Bad Guy” spent months topping streaming charts before radio embraced the song and made it a hit with a broader audience for even more months.

- “Heat Waves” by Glass Animals was huge among alternative fans before catching on with mainstream pop fans.

In most cases, however, the superhits are simply songs that a lot of people like and keep enjoying for a long time. It’s no surprise that almost all the superhits this century have been mainstream Pop, Pop Dance, Rhythmic Pop or Pop Hip Hop titles.

Such songs always existed. Until streaming gave us a way of measuring which songs people play when they’re in control of their music, however, we had no way of capturing them.

Had we magically possessed a way to gauge which songs people played from vinyl back in the day, we almost certainly would have uncovered many more superhits.

Five takeaways for radio…

1) Superhits always existed. We simply had no way of gauging which songs listeners still played for themselves for many months until streaming replaced buying music.

2) The biggest hits appeal to lots of people. For decades, experts have declared that fragmented music tastes would completely kill mass appeal. While the monoculture of the three-TV channels era is over, the extinction of the mass appeal hit in favor of the long tail simply has not happened. The songs that endure month after month do so because they appeal to a wide coalition of different people.

3) Burn is still a thing. For streaming services, people who have grown tired of a song aren’t a problem. They simply move on to songs they find more compelling. So long as enough listeners are not sick of hearing a song, it remains big. In radio, however, haters matter. Whether it’s because they’ve grown tired of a song or never liked it in the first place, haters change the station.

4) Timeliness still matters: Listeners may still personally love a song that’s over a year old. They may not even report being tired of it. If your radio station is in a currents-based format, however, your listeners expect your station to keep them on top of what’s happening right now in music. Keeping songs in heavy rotation for 18 months might not annoy your listeners in the moment, but it may undermine their perception that your radio station is on top of what’s happening today.

5) Using streaming data like other metrics is dangerous. As we outlined extensively, you have to learn new benchmarks for gauging songs’ streaming data because streaming measures song plays and because streaming mixes listening from both active and passive fans. How we measure music consumption is changing dramatically. People’s relationship to recorded music, however, remains remarkably unchanged.

Finally, is there a way you can spot a future Superhit early in its life? The biggest clue is that when listeners start streaming it, they don’t stop: Unlike most songs, superhits tend to cool off in streaming plays much slower than songs that follow traditional timelines. Ultimately, however, even if a song isn’t destined to be a superhit, if it’s a big hit today, you should play it today.