In our last Callout Summer School class, we examined how listeners’ reactions to songs translate into the five most common scores used to rate how much listeners love or hate a song. Now, we’ll tackle one of the most misunderstood and debated dimensions of how listeners fell about your music: Burn.

What question is Burn really trying to answer?

The idea behind Burn is that even if listeners love a song, they eventually get sick of it if they hear it over and over and over again. In gold-based formats, the stereotypical example is Stairway to Heaven, oft revered as the greatest song ever, but kept off many Classic Rock outlets for years because listeners said they had heard it one time too many.

In contemporary formats, programmers have traditionally used Burn scores to decide when to move a song from current to recurrent. The theory is that listeners have no idea what a “recurrent” is, but they do know when they’ve heard a song one time too many.

There are two fundamental problems with using “are you tired of this song” as a proxy for “should we move this song to recurrent”.

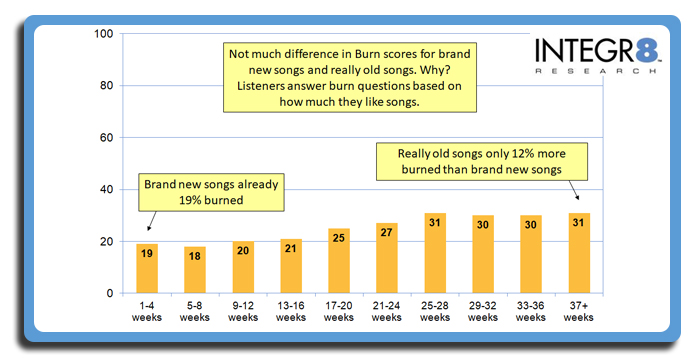

1) Burn often simply reflects appeal: As we explored in a past post, listeners often answer the question not based on how much they’ve heard the song, but instead on how much they personally like the song. If she just told you she loves a song, how could she ever be “tired” of it? If she hasn’t yet warmed up to a brand new song, however, hearing it just once is one time too many.

Traditional Burn score for the average CHR/Hot AC title (by songs’ vintage on the Billboard Hot 100 chart)

Many veteran programmers and consultants have long understood this problem and recommend ignoring Burn entirely. “Just look at how many listeners love the song and play those songs most often. When listeners stop liking it, stop powering it.”

This approach ignores the second problem:

2) Listeners want contemporary radio stations to play contemporary songs: People turn to a contemporary radio format because they expect to hear music that represents what’s happening right now in popular culture. If you promise your listeners “Today’s Hit Music,” but you mostly play songs that are several years old, that broken promise will ruin your reputation—and with it eventually your ratings.

While many songs run their course, some hits remain highly popular for years. During the last decade, One Republic’s “Counting Stars”, Gotye’s “Somebody That I Used to Know” and Ed Sheeran’s “Perfect” remained among the best-testing titles long after anyone considered them “current”.

Just because listeners still love a song doesn’t mean they consider it relevant.

So what do you do about this conundrum?

How not to get burned by Burn

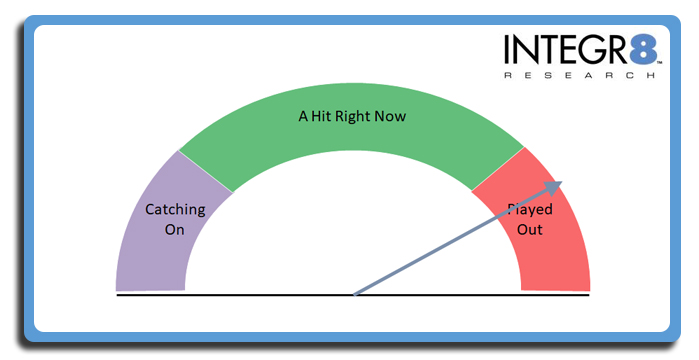

For our Integr8 New Music Research clients, we developed a proprietary measure called Hitcycle®, which tells you how listeners perceive the momentum of each song, regardless of whether they personally like it or not. Hitcycle provides clarity on when it’s time to move a big hit from current to recurrent.

Unlike old-fashioned Burn measures grafted from gold-testing techniques, Integr8’s Hitcycle is designed specifically for callout—and the need for contemporary formats to understand if a song still represents the “here and now” of popular music.

If your callout research uses an old-school Burn measure, however, here are four tips to use it effectively:

1) Understand how your research asks listeners about Burn: Although we speak of “Burn” singularly, there are at least four common ways of asking Burn—with each one yielding a different result:

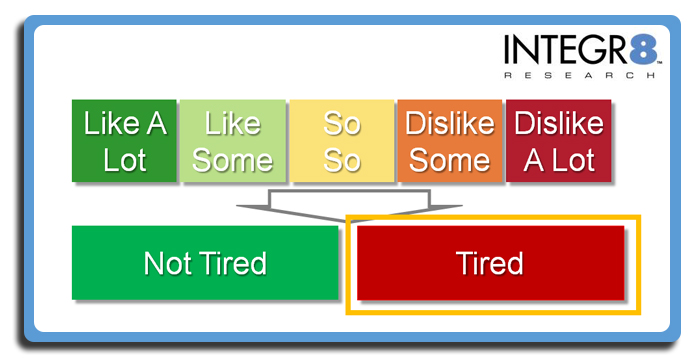

- Some researchers simply ask if you’re “tired” of hearing a song on the radio. The percentage of listeners who say, “yes”, I’m “tired” of hearing that song is then reported as the Burn score. A Burn score of “30” simply means 30% of listeners who know the song are tired of hearing it.

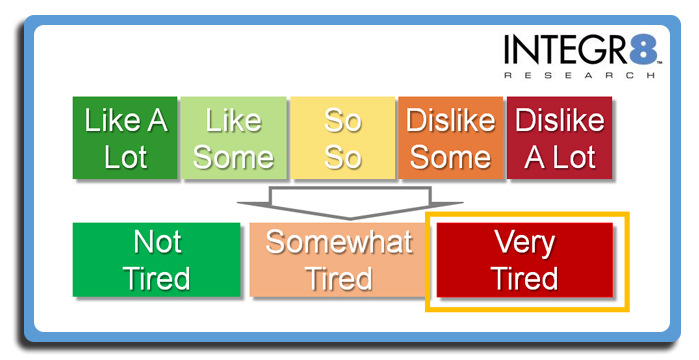

- Other companies ask if a listener is “very tired”, “somewhat tired” or “not at all tired” of hearing a song, reporting the percentage of listeners who are “very tired” of hearing a song as the Burn score. In this measure, “30” means 30% of your listeners aren’t merely sort of tired of hearing a song, they’re really REALLY tired of hearing a song.

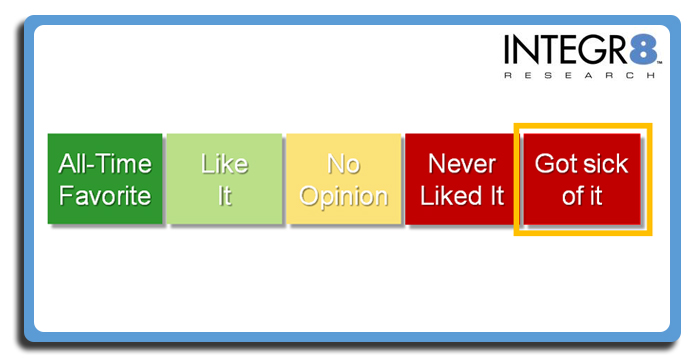

- While some ask Burn as a separate question from the song rating question, other companies measure Burn by making it an answer in their song rating scale. This approach forces listeners to choose if their weariness of hearing a song outweighs their fondness for that song. Callout vendors that take this approach often call Burn “DDL” or “Developed Dislike”.

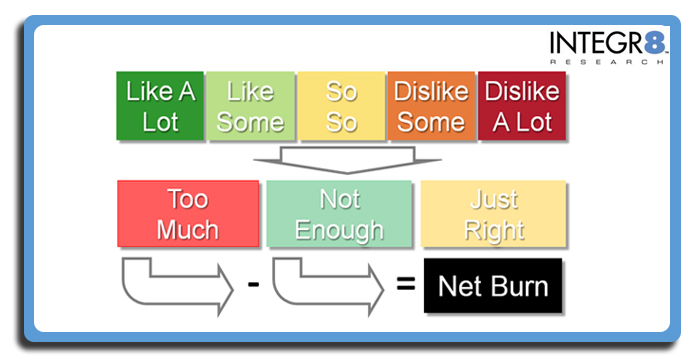

- Finally, some researchers who think Burn is inherently a negative question put a positive spin on it by asking listeners if they’re hearing a song on the radio “too much,” “not enough, or “just right”. Programmers examine if the “too much” score is higher than the “not enough” score to determine the Burn level.

2) Forget the 30% rule: Many programmers have heard a Burn score of 30 or higher means a song should no longer be a current. However, there’s nothing magical about 30%. If 30% of listeners are “tired” of hearing a song, then 70% of your listeners are not tired of hearing a song (or at least not very tired of hearing it.)

3) Interpret Burn scores with your station’s strategy in mind: What really matters is how important it is to your station’s strategy to be a source for new music. If you’re a rhythmic-leaning CHR whose strategy for dethroning your musically-cautious CHR competitor is to be more on top of the biggest hits, use a lower Burn threshold to move songs more aggressively out of currents. If, however, you’re a Hot AC whose strategy is to play proven hits to an adult audience, allow songs to have higher Burn.

4) Examine how long listeners have been hearing the song: Based on observing the listening patterns of on-demand audio listeners—specifically when listeners who are in control of their music stop playing big hits as often—we offer guidelines on when different formats should move songs to recurrent in our post “When Should Big Hits Become Recurrents?” In making this decision, it’s also vital to understand how often listeners actually hear the hits on your station and in the market overall.

Our next lesson on the Callout Summer School syllabus with tackle the other end of a song’s lifecycle by examining familiarity—specifically how to use familiarity data in callout with brand new titles.